|

A version of this post originally appeared on March 11, 2023.

Samuel R. Delaney is one of the pioneers of modern science fiction. He's garnered critical and popular success in his long career, an especially impressive achievement given his race. Black authors are still rare in science fiction, yet Delaney won his first Nebula in 1966. Wanting to correct this gap in my SF knowledge, I started with Babel-17, in no small part because it is narrated by Stefan Rudnicki, whose voice improves any story. In this space opera, the main character is a pilot turned poet, and she is a major celebrity, because in this universe, poetry is a big deal. (This is difficult to believe, but science fiction requires us to accept outlandish ideas.) The military has hired this poet to break the code of Babel-17, the language used by the enemies in a protracted intergalactic war. And thus we get a story with lots of space battles punctuated by discussions of phonemes. While I didn't fall in love with the book, I admired it, and I'd like to go back and read more of Delaney.

0 Comments

A version of this post originally appeared on March 4, 2023.

For Women's History Month, meet Charity Bryant and Sylvia Drake. Charity hailed from an erudite family--she was aunt to William Cullen Bryant, known for "Thanatopsis" and other poems--but Sylvia was no slouch herself, and they wrote reams of letters over the decades. From this correspondence, historian Rachel Hope Cleves reconstructs how two lesbians lived as a married couple in 19th century Vermont. I will confess I zoned out occasionally--many of the letters took the form of poems, and there is only so much early American poetry I can take--but I was glad to discover the Bryants' story. There is a lot of drama here. Before meeting Sylvia, Charity was popular with the ladies, and I can't forgive how she done Lydia wrong. There's also a lot about the social life, religion, and lifestyle of people in the decades following the Revolution. For one thing, people generally were more accepting of a same-sex marriage than I would have guessed. Of course there was some prejudice, and the two women themselves struggled to reconcile their lesbianism with their religion, but they were not pariahs. Far from it: they were esteemed members of the community. Remember this the next time someone claims that gay marriage is a recent invention. A version of this post originally appeared on February 25, 2023.

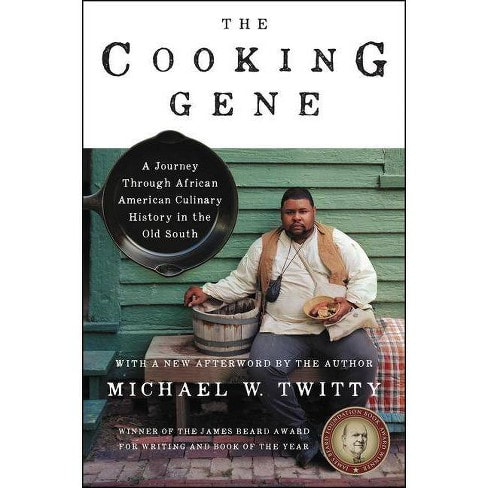

With The Cooking Gene, Michael W. Twitty writes a book that's not quite like anything I've read. He blends culinary history, memoir, genealogy, family history, Black history, social justice, spirituality and religion, and travel, delivered with prose that often verges on the poetic. It's hard to summarize. This is the story of how African food became African-American, but it's also the story of how one man learned more about his place in the world: by cooking traditional foods with traditional methods, by studying census records and historical newspapers, by exploring the limits of DNA ancestral discovery. Though Twitty celebrates soul food, do not mistake this for a joyful book. He mines four hundred years of trauma and violence to write this story. I was emotionally taxed as I read it, and it's not my ancestors who were enslaved. I recommend the audio. Twitty narrates with a mid-Atlantic Black accent that adds to the experience. A version of this post originally appeared on February 18, 2023.

I revisited a favorite, The First Fifteen Lives of Harry August, the novel that got me into Claire North. This time around I read it as an audiobook, and may I observe that Peter Kenny is excellent. North has this habit of sending her characters around the globe, and Kenny narrates the accents from six different continents like it's nothing. I bet he could do penguin accents if it came to that. Harry is born in England in 1919 and is adopted by Mr. and Mrs. August. He serves in the second world war and proceeds to live an unremarkable existence. Things only get interesting after his death, when he is reborn into the same circumstances: same year, same location, same birth parents, same adoptive parents, same soul. By age three, when memories of his first life begin to resurface, the young Harry goes mad. This is a common reaction for members of the Cronus Club, those rare individuals who recycle their lives, though Harry doesn't learn of them until life number three. It's such an enchanting premise: what would you do if you could learn from your mistakes, if death held no sway over you? It's a captivating thought experiment, though an unlikely plot for a novel. Characters who don't fear death get tiresome after a while. Fortunately for the sake of the narrative, a character named Vincent develops a technology that can wipe the memories of Cronus Club members, thereby upping the stakes from trivial to existential. In the process, he is accidentally destroying the world. Also he's Harry's best friend. North's characters are prone to getting into abstract arguments, debating their way through topics with whole philosophical essays that pass for dialogue. This is not a criticism. It's my favorite part of science fiction, where you get to muse over unexpected What If scenarios. A version of this post originally appeared on February 11, 2023.

In 1822, a free Black man named Denmark Vesey planned a revolt that, if successful, would have liberated enslaved people in Charleston, SC. The book Denmark Vesey's Garden is not about that. Instead, scholars Ethan J. Kytle and Blain Roberts study the memory of slavery in Charleston and the United States. The book is about history, but more importantly, it's about how we shape and select the stories that we call history. Normally it's the victors who get to craft the narrative of war and its aftermath, but with the American Civil War*, the losing side got to write that history. And are still getting to: we're seeing right now how the political machine in Florida colluded with the AP Board to defang African American history in high school classrooms. *aka the War Between the States or, even better, the War of Northern Aggression. The battle to control the narrative of history goes back a long, long way. For instance: After the war, there was a group called the Society for the Preservation of Spirituals, composed of history buffs who performed the slave songs. This group consisted entirely of white ladies, who believed themselves better able to preserve and interpret negro spirituals than formerly enslaved people or their descendants. It is not cultural appropriation every time a white person sings a Black song, but this? The ladies of the Society for the Preservation of Spirituals acted like they invented cultural appropriation. Then there was Miriam B. Wilson, born in 1879 in Ohio and raised to understand that chattel slavery was, you know, morally wrong. Then she moved to Charleston and went native. With the paternalism that characterizes so many white people to the present day, she opened the Old Slave Mart Museum and used it to soften the image of slavery. On viewing an image of an overseer with a whip, she concluded that whips weren't necessarily used on people. And while it is true that some slaves had whip marks on their backs, she reasoned that these might have been tribal tattoos, or perhaps they'd injured themselves to garner sympathy with abolitionists. We all know someone--frankly we're all RELATED to someone--who has unfortunate interpretations of political and social reality, but this someone is not running the only museum about slavery in a city that was a major port in the Atlantic slave trade, now are they. A final example: you may be aware of the Federal Writers Project, part of the Works Progress Administration in the Great Depression. As one part of the FWP, historians interviewed formerly enslaved people to collect their oral histories. The interviewees often spoke highly of their former masters--but of course they did. The interviewers were white. They knew the consequences of telling the truth. But those times when they did feel bold enough to discuss the ugly truth of slavery, the historians assumed they were lying (because Black people are prone to fibbing. It's common knowledge). I enjoyed the audiobook, narrated by Tom Perkins, and I would like to take pains to observe that the authors and I overlapped at the University of North Carolina, which means we're practically friends. A version of this post originally appeared on February 4, 2023.

You know how some guys are reallllly into the Civil War or realllly into World War II? That's me with Russian history, though I want to stress that I do not dress up in period costume to reenact Pugachev's Rebellion. With Russian literature as my gateway drug, I went on to major in Russian history as an undergrad. I daydreamed about continuing my studies, though that would have been impractical since my knowledge of the language is limited to a few nouns (glasnost, perestroika, and vodka). Twenty* years after graduating college, I'm doing a self-directed study in Russian history, emphasizing cultural and social themes, though if you insist on discussing military history, this is the one area where I'm competent. Bring it. Partly this is so I can better understand Putin and his invasion of Ukraine. Partly it's so I can add verisimilitude to my in-progress historical fantasy novel. Partly it's because none of you are willing to play Pugachev's Rebellion with me. This study led me to Understanding Russia: A Cultural History, by Lynne Ann Hartnett. I picked up some good lessons from it, but the audiobook production values were disappointing, so I wouldn't necessarily recommend this unless you really dig Russian history. However! This is part of the Great Courses series of audiobooks and documentaries, and here I can make an enthusiastic recommendation. They've got something for everyone. Scholars present lectures on a wide range of topics at the undergraduate level, so it's like auditing a class. Your local public library may have Great Courses audiobooks or documentaries to check out or download for free, or you can purchase them from the publisher website or wherever else you acquire your media. *what the HELL A version of this post originally appeared on January 28, 2023.

George Saunders is in the very top echelon of my favorite writers. A literary fiction writer who leans hard into genre, he is arguably America's best contemporary short story writer, and his one novel, Lincoln in the Bardo, will stagger you. I'm getting into the yearly habit of reading him in January, to start the year out right. This year I read A Swim in a Pond in the Rain. It is not short stories nor a novel but... literary criticism! Of Russian literature! I know this is going to be a hard sell, but stay with me here. The book is just astonishingly good. It's like being in the best graduate level English class, only you don't have to write papers or read Derrida. Saunders helps us dive into seven masterpieces, helping us as readers articulate why we respond to the writing, helping us as writers study the craft. This book was such a joy. I kept making excuses to get to the audiobook--and please, if you're going to read this, consider going that route. Saunders narrates the discussion, while actors read the stories:

A version of this post originally appeared on January 21, 2023.

The Minotaur Takes a Cigarette Break (2000) features a protagonist who lives in the Piedmont of North Carolina. He works in the kitchen of a restaurant and lives by himself at the Lucky You mobile home court. He is handy with car repair and household fixes. He has the body of a man and the head and torso of a bull. I can be forgiven for expecting this to be a fantasy novel, based on the first two words of the title ("The Minotaur") but I ought to have known it would be a literary fiction novel, based on the remaining four words ("Takes a Cigarette Break"). I tend to be leery of literary fantasy novels, because they tend to have a light touch with the good genre stuff. But I read till the end, hoping the Minotaur would gore somebody or get trapped in a maze. Alas. Contemporary literary fiction is usually not my jam, particularly the slice-of-life subgenre that features the minutiae of daily existence, peppered with colorful character portraits. It's not to my tastes, but I can respect that Steven Sherrill did a fine job with it. I have no qualms recommending it, if that's your type of reading pleasure. Except: The main character is both disabled and disfigured, and there's no real reckoning with that. His primary disability is with speech. His bovine tongue struggles with language, so his verbal communication consists mostly of grunting. His disfigurement is that he's half man, half bull. And most people he encounters just sort of... roll with it? They're pretty chill? I can accept the premise of a monster from legend frying potatoes in a diner outside Lexington, sure, but I cannot accept that human beings are open and accepting of radical physical difference. Like. Has Steven Sherrill ever met any people, at all whatsoever. (For those of you wondering the inappropriate question, the Minotaur has an unremarkable human phallus. He is not hung like a Holstein.) Given my inconsistent relationship with literary fantasy, you should take opinions with a grain of salt. Droves of people love this book. (Droves. Ha. Unintentional cow pun.) I encourage you to try the audiobook. Narrator Holter Graham gets the accents right, which is rare in popular media. North Carolina accents are hard. I grew up in North Carolina and can't do a convincing one. And he packs a lot of expression into the Minotaur's limited vocabulary. I'm writing a manuscript set in 18th century Russia. I've got two failed novels already, but the setting of this third pre-fail novel is more ambitious than anything I've tried yet. I'll be reading a whole lot of books and articles about Russian history, literature, and culture, and while I promise not to subject you all to the whole lot of it, I'm going to write about the books that are good for a general, non-Russia-obsessed audience, starting with The Story of Russia, by Orlando Figes.

Though I love history as a subject, history books tend to lose my interest, due to dry prose and lack of interpretation. Telling me facts is not as important as building a narrative around the facts. Figes is good at this historical storytelling. He doesn't just tell us that rumors about Catherine the Great's death are untrue--there was no horse involved, well endowed or otherwise--he tells us why these rumors sprang up. The writing is more engaging than most of the history out there, particularly history of this caliber. Though a book about Russia over the centuries will not be to everyone's taste, it has unfortunate relevance. The book went to press in April 2022, two months after Putin invaded Ukraine. I can't image what kind of last-minute edits Figes made, but he does a fantastic job of explaining the historical and contemporary relationship between Ukraine and Russia, and he helps readers understand Putin's megalomania. I particularly recommend this as an audiobook. Stefan Rudnicki, one of my favorite narrators, was born in Poland and does authentic east European and Russian accents. A version of this post originally appeared on January 7, 2023.

Having finished my re-read of Stephen King's collected works of short fiction, I'm catching up on the novels I've missed in recent years, starting with Blaze (2007). King wrote this under his pseudonym Richard Bachman, partly because the prose style is so different from his normal style, which is conversational, luxuriating in details and subplots. For this noir crime novel, the prose is taut and lean, reminiscent of Jim Thompson (The Killer Inside Me). Blaze is a likeable, earnest main character with cognitive impairments, due to brain injuries from an abusive father. The violence done to him in childhood by his father, foster parents, and the headmaster of the orphanage explain why he goes on to do violence to others. He doesn't mean to hurt anyone. He just doesn't know any other way. King, or Bachman rather, was inspired by Steinbeck's Of Mice and Men, so if you want an uplifting book maybe try something else. It's a fine book, not one of King's masterpieces, but recommended for anyone who likes the dark, dirty, gritty subgenre of crime writing. |

Book talks

When Covid first hit, I started doing book talks on social media as a way to keep in touch with people. I never got out of the habit. I don't discuss books by my clients, and if I don't like a book, I won't discuss it at all. While I will sometimes focus on craft or offer gentle critical perspectives, as a matter of professional courtesy, I don't trash writers. Unless they're dead. Then the gloves come off. Archives

February 2024

Tags

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed