|

Tade Thompson’s Rosewater is one hell of a book, science fiction plus thriller plus horror. The prose is superb and the characters are uncommonly well developed.

There is so much plot going on here, so much, that I will not attempt a plot summary. It’s the year 2066, the aliens have landed in Nigeria, and consequently a few people are psychic now. That’s all you need to know. One scene stopped me in my tracks, and I do mean that literally. I was walking Revvie and when I finished listening I stopped, said “Holy shit” aloud, and rewound to listen again. For those who’ve already read it, I am of course referring to the part where the starving carnivorous floating alien gets loose. Last time I read a scene that good was in Cormac McCarthy’s The Road, when the father and son stumble across the horror basement. That’s the level of Holy Shit I’m talking about. The main character, Kaaro, is a dickhead. That’s also a risky move, but I hope I’m making clear that Tade Thompson has the storytelling chops for it. I’d also like to point out that we follow each other on Bluesky, which makes us best friends, basically. The prose is excellent. That’s the most important thing to me in any book, the wordsmithing. And the audiobook is a joy. I just looked up the narrator to confirm that Bayo Gbadamosi is from Nigeria, surely he must be with that accent but nope, he was born in London. Anyway the narration is terrific, though at some point I need to go back and read the book in print. What with all various times and dimensions and plot line, I need to be able to flip back and forth on the page. If violence is difficult for you to read, this is not the book for you. Cannot overstate that enough. I’m normally unfazed by fictional violence, but woof, this book got my attention. I learned about a form of death involving tires and unfortunately there is no way to unlearn that. I will have this knowledge forever. Also skip this book if you don’t like reading hot alien sex. Otherwise, strongly recommended.

0 Comments

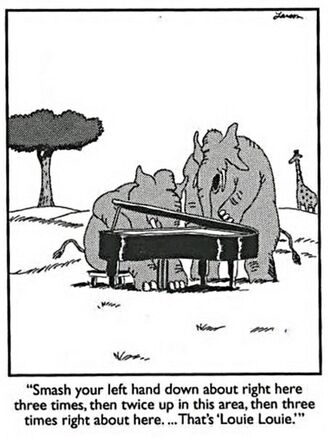

I read The Employees, a science fiction novel written by Olga Ravn, translated by Martin Aitken, and narrated by Hannah Curtis. First, a discursion. When discussing books, I go light on plot summary. A summary can tell you what happens, but that’s not a good indicator of whether you’ll enjoy the book. Better to describe the qualities of the plot. Are scenes action-packed with explosions and space lasers? Rooted deeply in the thoughts of a character? Predictable or experimental? Defined or ambiguous? Is the plot even the main appeal of the book? That’s common with commercial fiction, less common with literary fiction, and often irrelevant with nonfiction. Cookbooks don’t have plots. This logic sort of applies to music, too. “The Devil Went Down to Georgia” is a plot-driven song about good v. evil (though let’s be honest: the devil kicked Johnny’s ass in that duel). “Louie Louie” is about gibberish. Other elements can be more important than plot. Character is the other big one. I don’t especially care who gets murdered or whodunnit; the reason I enjoy Agatha Christie is because of Hercule Poirot.

Setting can be a major appeal factor. When I read historical fiction, it’s usually because I’m interested in that era or location. And for me, the single biggest factor is the prose style (and illustration style for graphic novels). I care more about how the story is told than what story is being told. George Saunders, who gets my vote for best contemporary American wordsmith, wrote a book of literary criticism and I devoured it. No one goes around devouring Harold Bloom. At least I hope not. Thank you for indulging my two-hundred-word excuse for not describing the plot of The Employees. I didn’t follow what was going on. I enjoyed the book, but I’m not real sure what it was about, beyond humans and humanoids interacting with alien objects on a space ship. Nor can I name a single character. In The Virgin Suicides, Jeffrey Eugenides uses a collective narrator, a technique that left me feeling off kilter. Same disconcerted feeling here. I never got my bearings. But I enjoyed it! The book was atmospheric and moody and weird, more literary than I normally go for, but it was a short book so I felt willing to try something strange. I didn’t love it, the way I adored the atmospheric and moody and weird writing of Jeff VanderMeer’s Annihilation or Susanna Clarke’s Piranesi, but I’m glad I spent time in that world. I draw a distinction between good writing and good storytelling. Not every author is good at both, and commercial publishing favors the latter. Plot-driven books sell better than language-driven.

Personally, I look for strong, competent prose. I don’t need ornate language or undreamt-of metaphors, but I will stop reading for mechanical clumsiness: overusing dialogue tags, slipping artlessly into comma splices, beating that subject-verb-object triple play for every dang sentence. Adrian Tchaikovsky delights on both counts, writing and storytelling. He’s best known for his Children of Time series, but I got started with Elder Race, a quick read with excellent audiobook narration by John Lee. It’s a perfect genre blend of fantasy and science fiction. An overlooked younger princess goes on a hero’s quest to find a wizard to save the realm from a demon. The wizard is in fact an anthropologist second class, living out whole centuries in suspension while he waits for his fellow scientists to retrieve him from his outpost. It hits all my favorite notes: thoughtful internal character development, adventure tempered by human politics, magic clashing with technology. And no goddam romance. Sorry—but I don’t like love stories in my fiction. That’s a tender spot for me. The depressed and lonely weird wizard dude with literal horns growing out of his forehead, thanks to futuristic body mods, does not end up with the courageous and beautiful young woman. Like they don’t even flirt. It’s wonderful. There are any number of reasons why you might not like a genre. I just explained why I don’t like romance novels, so I’m in no position to hector anyone about not reading science fiction or fantasy. But if the reason you abstain is because you’re only familiar with shoddier examples, I’d invite you to give speculative fiction another go. This one will only take a few hours of your time. Bloodchild collects seven stories and two essays by Octavia Butler. She died in 2006 but remains a fixture of science fiction and fantasy.

Of these stories, my favorite was “Amnesty,” about humans adapting to extended-stay alien visitors. The story invites you to consider if and how you would resist invasion. The whole story was strong, but the last couple of lines left me all shook up. But all of the stories are strong, with themes of illness and alien encounters show up repeatedly. And the essays are about Butler’s life and her thoughts on writing. They’re lovely. I quite enjoyed the audiobook as narrated by Janina Edwards. It’s a quick listen or a quick read, and a good entry for readers who aren’t familiar with Butler. I listened to Black Indians (1986; rev. 2012), written by William Loren Katz and narrated by Bill Andrew Quinn. It examines the intersection of Black and indigenous cultures in North America and what would become the United States.

Okay, I just looked it up and Katz died in 2019 (age 92!) so it won’t hurt his feelings if I criticize the book a little. I was hoping for more discussion of the broader themes of race and culture, but that is perhaps a contemporary bias. I shouldn’t expect much sociology in a forty-year-old history book. A kinder perspective would be to appreciate that Katz, a white man, did scholarship about minoritized groups well before that was common in the literature, even if it does wander sometimes into the noble savage stereotype. Katz is strongest when speaking about individuals. Of the people he describes, three stand out:

I read bell hooks’s Ain’t I a Woman: Black Women and Feminism (1981), with audiobook narration by Adenrele Ojo.

When I was an undergraduate, we learned that the first wave of feminism (focused on women’s suffrage) and the second wave of feminism (focused on women’s liberation) served middle and upper class white women to the exclusion of others. By the time I came along as a Women’s Studies major in the early 2000s, the curriculum had a strong focus on inclusivity. Those gains are due in no small part to hooks. Though the term intersectionality wasn’t yet in the scholarly parlance, hooks anchored Ain’t I a Woman on the intersection of race and sex, with class and labor making frequent appearances. Three takeaways: One. Elizabeth Cady Stanton, like so many early feminists, was anti-slavery but not anti-racist. She wanted Black people free from chains on religious grounds, but she did not think of them as equals. I know we covered this when I was in college, but either they weren’t emphatic enough or I distorted the message. It would have been in character for me to tamp it down, to apologize for her (she meant well, she was doing the best she could for the time, etc.). Nope. Lady was a straight-up racist. Abolitionists can be racist. Two. The labor forces have changed so much, so quickly. I was born in the year hooks published the book, 1981. hooks devotes ample time to the idea of women in the workforce, because that was still one of the big social questions of the time. Yet it already seemed hopelessly outdated when I was growing up, the idea of women staying at home, expecting a man to provide for them. Capitalism was happy to assist with that social change. That sped things along. Laborers who earn less but control more of the household spending decisions? Let’s flood the workforce with them! Final takeaway: then, as now, our social movements cannot afford to exclude people’s needs. “Let’s fix patriarchy first, and then we’ll focus on sexism. Let’s solve poverty first, and then we’ll worry about accessibility.” No. We lift up everyone or we lift up no one. If I had the power to compel 330 million Americans to read one and only one book, it would be The Autobiography of Malcolm X (1965).

When I first read it as an adult, I knew Malcolm X was a controversial figure in the civil rights movement, but like most Americans, my high school education focused on the Greensboro Woolworth’s sit-ins, Rosa Parks, and Dr. King’s “I have a dream” speech—all the parts that are palatable to contemporary school boards. I did not know what to expect. It is a vivid document of race and religion in the twentieth century, but it’s also a thumping good story. When he is a child, Malcolm’s father is murdered, his mother hauled off to a psych ward. After some time in the Michigan foster system, he goes to Boston to live with his sister Ella, who is such a charismatic figure that she nearly outshines Malcolm in his own autobiography. The next few years are one big party, filled with alcohol and drugs. He takes a job shining shoes at a club, where he hears Peggy Lee when she first makes it big. He hangs out with his buddy Redd Foxx. He socializes with Billie Holiday, as one does. He takes his white girlfriend out dancing. He sells drugs. He robs rich people. Inevitably he is caught. It is in prison that he discovers the Nation of Islam. It transforms him. It is also in prison that he begins to read. He devours books, giving himself the education he never got in school. After his release, he becomes a minister in the Nation of Islam. He teaches that white people are white devils. He opposes integration. He gains fame as a spokesman for the Nation of Islam. For seven years he devotes himself to his religion, until he has a falling out with the leader, Elijah Muhammad. And then he travels to Mecca and has an epiphany. On seeing faithful Muslims of all colors, he realizes that white people are not devils, or at least not all of them. He returns to America and begins teaching from this new place of understanding, though he struggles to shed his old reputation. The book was written by journalist Alex Haley, based the book on interviews he conducted with Malcolm X. I particularly enjoyed the audiobook, narrated by Laurence Fishburne. I’m going to close with two passages: “My greatest lack has been, I believe, that I don't have the kind of academic education I wish I had been able to get—to have been a lawyer, perhaps. I do believe that I might have made a good lawyer. I have always loved verbal battle, and challenge. You can believe me that if I had the time right now, I would not be one bit ashamed to go back into any New York City public school and start where I left off at the ninth grade, and go on through a degree.” “I have given to this book so much of whatever time I have because I feel, and I hope, that if I honestly and fully tell my life's account, read objectively it might prove to be a testimony of some social value.” George Saunders is the best contemporary American writer, an opinion I feel more comfortable holding following the deaths of first Toni Morrison and then Cormac McCarthy.

Unusually among successful writers, his primary medium is short fiction. He’s only got the one novel, Lincoln in the Bardo, which is so good that he should probably stop there. Pastoralia is his second collection of short stories, published in 2000. Prose craft is different from storytelling. Being good at either one of these things is uncommon. Each Saunders sentence writes is a gem, but handled in such a lowkey way that you don’t realize you’re reading a master. You’re too focused on turning the pages because you need to know what happens next. Though if you enjoy audiobooks, I would implore you not to turn the pages but to listen to Saunders narrate his own work. The thing about Saunders that too many reviews miss is that he’s funny. Uproarious. The man is funny in print, but I listened to the book and I was howling. Also: when you listen, you can’t look ahead to know when a story is about to end. Three different times in this book, a story ended and I gasped out loud in shock. There are only six stories so that is a fifty percent gasp rate. My favorite story was “Pastoralia,” about some historical reenactors, but the one I’m going to quote from is “Sea Oak,” in which an elderly aunt bullies her nephew (a sex worker) into earning more money: “Show your cock. It’s the shortest line between points.” In now the sixteenth month of my unusually isolated lifestyle, following a general history of being not outgoing whatsoever, I find myself reading more about social connections, either why we need them or how to forge them. This led me to Lydia Denworth's 2020 book Friendship: The Evolution, Biology, and Extraordinary Power of Life’s Fundamental Bond, audiobook narrated by Tiffany Morgan.

Though I've read a lot of popular nonfiction about human relationships, most of those books have been more on the social science side of things. This introduced me to research I was unfamiliar with. One finding: friends have brains that process the world the same way. It turns out that we do not all experience music in the same way, for instance. Friends are more likely to have similar brains that lead them to enjoy the same types of music. Or put another way, shared interests are more than just superficial commonalities. They speak to similar brain structures. I find that many of these books are written by extroverts who just...don't quite get it. I like extroverts. Some of my best friends are extroverts! But I am not sure I trust the social advice of people who understand the words "dinner party" beyond the abstract. My other frustration was that discussion of social media was shoved into one chapter, as though it were still a niche consideration in friendships. And within that chapter, the advice was that social media should supplement friendships, but that you should spend more time with people in real life. Excuse me, I am right here! Excuse me! Of course I would prefer local friends. Spending time in the same room is valuable, even if you're just hanging out instead of talking. Also there are certain activities that cannot be managed satisfactorily without proximity. But the author seems unaware that many friendships start online. My closest friends are people I have not met. Not met yet, rather. I want to read one of these books written by someone who is Very Online. These mild concerns notwithstanding, I enjoyed the book. I broadly recommend it, because social connections are so important for a healthy and happy life, for all of us, even the hermit-in-the-snowy-woods types like me. After seventeen years, I’m rereading Terry Pratchett’s Discworld series, and I hope you’ll consider joining me. These are books that will make you feel better. You will leave them knowing more about yourself and other people, and you will feel less pessimistic about everything.

I’m reading these in chronological order, which is why I’ve got Color of Magic up first, but that’s not where I recommend people dive in. With more than forty books in the series, there are a ton of great entry points, since few of the books depend on familiarity with prior entries. I do think the stand-alones are less intimidating, perhaps. Small Gods is my standard recommendation. But let’s not sweat the details. If you’ve never read Pratchett and you were waiting for a sign, hello, here it is, the universe would like you to read a Discworld book. The Color of Magic introduces us to the greatest city on the Disc, Ankh-Morpork, and its least talented wizard, Rincewind. Until I moved to a state with unjustly few characters allowed for license plates, my license plate read WIZZARD in homage to Rincewind. In some ways he is my favorite Discworld character, not because he is the best, but because I imprinted on him like a duck. I’m not doing anything like a coherent plot summary, but that’s not the point. No other author’s death has affected me more than Pratchett’s. That’s what his books have meant to me, and so many other people, but I am afraid if I keep on in this vein I will sound like a religious fanatic. Occasionally I’ll be discussing these books on Sundays (the new Day of the Week for these weekly book talks), or they might come midweek if I’ve got another book to discuss on Sunday. But I will write about each one. I intend to read a bit of Pratchett each day until I have finished the series, however many months or years that takes. |

Book talks

When Covid first hit, I started doing book talks on social media as a way to keep in touch with people. I never got out of the habit. I don't discuss books by my clients, and if I don't like a book, I won't discuss it at all. While I will sometimes focus on craft or offer gentle critical perspectives, as a matter of professional courtesy, I don't trash writers. Unless they're dead. Then the gloves come off. Archives

February 2024

Tags

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed